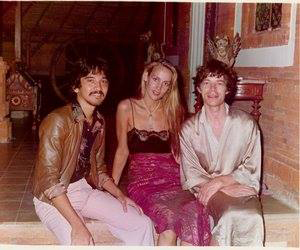

Why did you come to Bali? We asked Diana Darling to dissect a generation of island refuseniks who made the move more than three decades ago. Images: Oscar Munar. Styling by Angie Anggoro.

Seated, left to right: Bruce Carpenter Collector and connoisseur of Indonesian tribal art. Cynthia Hardy Muse, businesswoman and co-visionary with her husband John. Amir Rabik Entrepreneur and host to the stars. Jean Howe California-sunshine carrier and co-founder of Threads of Life. Leonard Lueras Writer, publisher, and consumer-researcher for Bintang beer. Standing, far right: Arthur Karvan Founder of the famous Arthur’s club in Sydney; designer of fashion fabrics and boutique residences Standing, left to right, back row: Emerald Starr Chocolate entrepreneur and developer of spiritual resorts in bamboo. Pintor Sirait Sculptor in steel and expert best friend. Milo Fashion designer, devoted son, and celebrity host. William Ingram Co-founder and chronicler of Threads of Life; former computer geek. Ananda Hart Painter and socialite; former Hollywood movie star super-hero. Ian van Wieringen Painter; expert on long-legged beauties.

FOR one thing, we were young. Even so, most of us already had a past. Some of us had recently been in the movies or bereaved or divorced or bankrupt or had just got out of jail. Most of us had been travelling for a while – often rough, sometimes dangerously.

Everyone was good at something, although some hadn’t yet discovered what it was. Everyone was looking for something, even if they didn’t know exactly what it was.

Some were looking for a sort of perpetual high, where the air was always gentle and there was always someone cool down the beach or at the next table, and no one would bother you about who you were or how you spent your days and nights, and if you ran out of money it was easy to make some more, if only enough for the next week.

Some of us were just looking for something to do. Some of us were looking for a cheaper place to do what we were already doing. Some of us were looking for each other. None of us would have said at the time that we were looking for ‘healing’.

We were all sorts of people – actors, scholars, con artists, filmmakers, fashion mavens, lawyers, fortune-tellers, potters, musicians, mystics, chefs, beach bums, heiresses, poseurs, photographers, traders, painters, stockbrokers, surfers, dancers, published and unpublished poets, and publishers, too. Some were good at taking rich people around the archipelago. Everyone had a go at designing something; some made a fortune at it.

John Hardy had legendary success designing jewellery when he teamed up with his wife Cynthia. “He had the ideas, I had a business model,” she once said. Neiman Marcus, a high-end retailer, saw one of his silver key chain ornaments and said, basically, “Can you make us a gazillion of these as earrings?” They did, and John Hardy became a worldwide luxury brand.

Before the late Linda Garland became “the bamboo queen”, she designed nice things for the home, made by Balinese artisans. Her genius lay in persuading rock stars and tycoons that they needed these things. She decorated homes for David Bowie and Sir Richard Branson. Everyone who was important adored her.

And the much-missed Madé Wijaya, né Michael White – who famously arrived in Bali in 1973, having jumped ship and swum ashore in a storm – designed beautiful gardens for resorts and moguls all over Southeast Asia. But his brilliance was his uncanny understanding of Bali.

Each of us had a private Bali, peopled with Balinese friends and families, who gave us a place to live and opened up worlds to us, introduced us to young craftsmen and old sorcerers, took us to holy places, and showed us the way to behave around ‘the gods’. They taught us the gamelan tuning systems and how to carve masks and make them come alive in the dances.

Perhaps we took our Balinese friends on tour to New York or India. We helped with their medical bills, and many put the children of their Balinese families through school. When our Balinese friends died, we went to their house; later we gathered in a corner of the graveyard, smoking kreteks with the gong orchestra.

As expats, we were not nearly as nice to each other as we were to our Balinese friends; but then, unlike the Balinese, life among us was unstructured. Some people were extroverts and threw ‘full moon parties’ where everybody had to wear white.

Others were introverts and avoided foreigners, often irritating other expats by punctuating their speech with Balinese slang.

We used to gather at places like Murni’s, Mak Beng, the Tandjung Sari, the Blue Ocean and Madé’s Warung. We got our mail at the poste restante of the local post office. (The late Shane Sweeney, a seminal expat, once waited for months for an important letter, only to find it filed under “M”, for “Mr.”) We shared tailors and sent each other presents with our driver, if we had one. When we started having children, some expats started schools, and later organic farmer’s markets. All the expat kids had Balinese children’s rites. Madé Wijaya said of the sons of Linda Garland and Amir Rabik that they had full Anak Agung wardrobes.

Snob appeal was varied, depending who you were. For some it was simply a matter of making a pile of money and spending it on building a fabulous house. For others it was having chic Balinese friends – venerable dance masters or priests or artists, or princelings in the government. In some circles, it was cool to be able to read Balinese script or to be treated for black magic. Status symbols also varied. Everyone appreciated heirloom keris and rare Balinese textiles, and a few could wear these things with flair. What you drove, on the other hand, was never a big deal. It was more impressive to have a driver who could negotiate the bureaucracy and possibly wrangle snakes.

Anthropologically, we felt a tribal kinship of oppression under Indonesia’s murky immigration laws; and we were serially polygamous. Our culture prized achievement and gratification. There was no point in being political, because we were foreigners and could be expelled on a whim. But as we got older, people became engaged with problems facing society and the environment, and many expats now work with Balinese in charitable foundations.

Today, as the group shot here shows, the early expats are still sexy. The man-eating divas may have gone vegan, but the fire of life is still blazing.