Gava Fox gets to grips with the facts about fibbing.

The great American writer Mark Twain is frequently credited with saying “a lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes”.

Ironically, he never said it.

Metaphors regarding the momentum of mendacity and the tardiness of truth have a long literary history, but the real author of the expression is said by academics to be the English satirist Jonathan Swift, writing in 1710 that “falsehood flies, and the truth comes limping after it”.

The truth is everyone lies, but why do we do it, when do we do it, how did we learn to do it, and is it ever acceptable?

Biblical literalists will tell you the first lie was spoken by Satan in the slithering guise of a serpent in the Garden of Eden when he told Eve “ye shall not surely die” if she ate the forbidden fruit. It wasn’t instant death that God had threatened, but rather the loss of immortality, and Satan’s forked tongue meant from that day forward humans would know the difference between good and evil – a loss of innocence that would result in millennia of conflict.

One of the 10 commandments specifically addresses lying – thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour – yet the Bible contains dozens of examples of mendacity in both the old and new testaments including, non-believers say, the biggest of all: Mary’s claim of immaculate conception.

In the 5th Century, Saint Augustine of Hippo argued that every lie was a sin and every sin should be avoided. Even lies told with the best of intentions were still sins.

Augustine, of course, lived in the Dark Ages, the period of economic, demographic and cultural stagnation that followed the fall of the Roman Empire. A lie could apparently be detected by touching someone’s tongue to a red-hot poker; if it stuck and burned, it was a lie, but if the accused escaped unscathed, they were telling the truth.

There is some veracity to that test. Science has shown that we are likely to become dry-mouthed when lying, but telling the truth provides the saliva necessary to insulate against being scorched.

It was during the Renaissance that people first began to become more realistic about what it takes to get on in the world. Lies became part of the fabric of society.

As regional kingdoms proliferated, they attracted obsequious courts that served only to flatter the monarchy in the hope of royal reward.

The system is best summed up by the Hans Christian Andersen story “The Emperor’s New Clothes” about a pair of tailors who promise his imperial highness a suit of clothing that will be invisible to anyone unfit for their position.

Of course they dress the Emperor with nothing, but as he walks naked before his subjects they nevertheless lie by telling him he is wearing the most beautiful outfit ever seen.

It is only when a child shouts “but he is wearing no clothes at all” that the charade is exposed. The Emperor still continues his procession, fearful that admitting the truth would show him to be an unfit ruler.

In the movie “The Invention of Lying”, British comedian Ricky Gervais presents a world where the idea of even the most innocent white lie doesn’t exist. It makes for cruel watching.

When the protaganist asks his blind date “how are you”, she replies “disappointed that you are short and fat with a snub nose”. An advert for Coca-Cola proclaims “it has too much sugar and can give you diabetes”, while a tramp holds a sign reading “I’m lazy and alcoholic and will spend your money on booze”.

Then the character played by Gervais has an epiphany and learns to lie, with tragicomic results.

At first he lies only for good. He convinces his dying mother that paradise awaits, he talks a neighbor out of suicide, and stops a friend from being arrested.

But things escalate rapidly.

Spotting a beautiful women walking in the street, he tells her “the world will end unless you have sex with me”.

“Oh my goodness,” she replies, “do we have time to find a motel or should be do it right here on the pavement?”

The denouement comes when Gervais, a very public atheist in real life, has his character invent religion as he grows more comfortable in lying. As he teaches others to follow suit, social cohesion breaks down and it is only when everyone learns to lie that normalcy is restored.

Bella DePaulo, one of the world’s leading experts on the subject, says most adults lie at least one or two times a day.

There are basically four reasons why people do it – to protect themselves, to promote themselves, to affect others (either in a good or bad way) or for pathological (disease-caused) reasons.

Most lies, DePaulo says, are intended to protect the feelings of others. For example, as every man knows, there is only one correct answer to the question “does my bum look big in this”?

While anyone would consider this a very minor fib, studies by DePaulo and colleagues suggest most people at some point will tell one or more serious lies, such as denying an illicit relationship or making false claims on a job application.

In his scholarly essay “Why we lie: The science behind our deceit”, author Yudhijit Bhattacharjee says the universal talent for deception shouldn’t surprise us.

Researchers speculate that lying as a behavior arose not long after the emergence of language and the ability to manipulate others without using physical force likely conferred an advantage in the competition for resources and mates, akin to the evolution of deceptive strategies in the animal kingdom, such as camouflage.

He quotes Sissela Bok, an ethicist at Harvard University and one of the most prominent thinkers on the subject: “Lying is so easy compared to other ways of gaining power. It’s much easier to lie in order to get somebody’s money or wealth than to hit them over the head or rob a bank.”

But while everyone lies, not everyone is good at it.

According to experts, liars frequently give themselves away with visual or verbal clues. If someone touches their face – particularly their nose – there is a good chance they are not telling the truth. If someone moves objects between you while you’re talking, they are likely hiding something. If someone uses contractions less often than normal in speech – saying “I did not” instead of “I didn’t” – they are likely trying to make you believe a falsehood.

In fact, less than five percent of people are what you might call accomplished liars, but that doesn’t mean we aren’t taken in by many more untruths. The reality is human nature means we tend to believe what people tell us.

“If you say to someone, ‘I am a pilot,’ they are not sitting there thinking: ‘Maybe he’s not a pilot’,” wrote Frank Abagnale, whose talent for impersonation and forgery was the inspiration for the Leonardo Dicaprio movie “Catch Me If You Can”.

“People are not expecting lies, people are not searching for lies. A lot of the time, people want to hear what they are hearing.”

As an idea for a still-to-be-published book called “The Complete Kant” – a reference to the eponymous philosopher’s claim that every lie was morally wrong – Welshman Cathal Morrow spent a year in which he claimed he never lied once.

This, of course, proved difficult – telling his four-year-old there was no Santa Claus was particularly tough – but overall his relationships with family and friends improved significantly, he said.

Scientists say that children learn to lie between the ages of two and five, and while the behavior may infuriate parents, it is actually a sign that their developmental growth – like walking and talking – is on track.

Studies suggest that people lie most between the ages of nine and 17 – often creating absurd whoppers – but truthfulness increases with age as our actual achievements catch up to our boasts.

It’s those who never stop lying that become sociopaths, but a surprising number of them live fully-functioning lives – usually as politicians.

America’s first president, George Washington, is famously mythologized as saying “I cannot tell a lie … I did it with my little hatchet” when confronted by his father about damage done to a cherry tree.

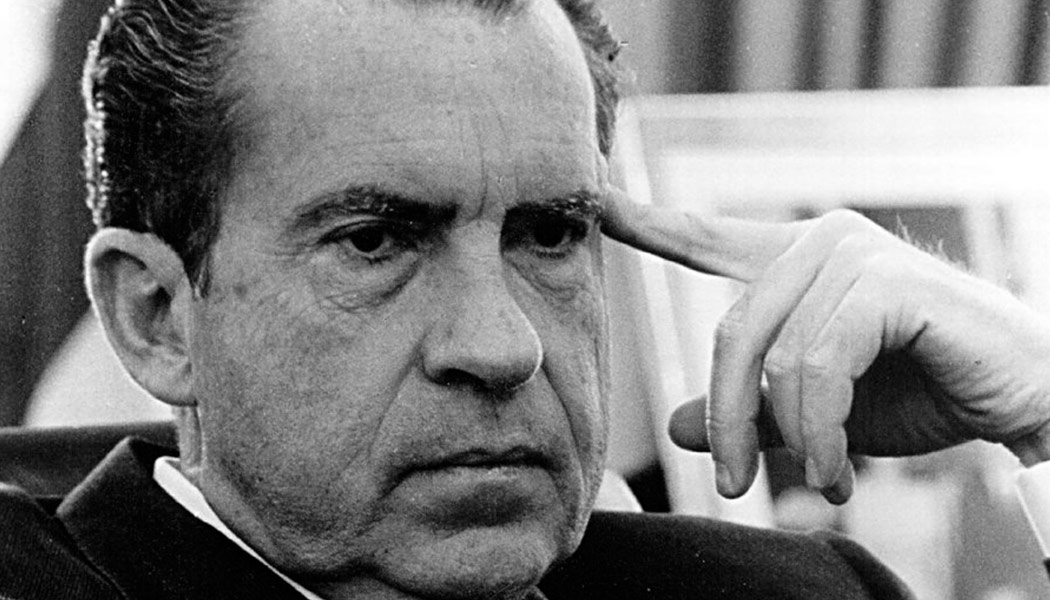

The White House, however, has long been the birthplace of scandalous lies.

Richard Nixon resigned in disgrace in the ’70s as a result of the Watergate scandal when he denied knowledge of the affair by proclaiming “I am not a crook”.

Two decades later, Bill Clinton narrowly survived impeachment despite blatantly lying about a relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

“I did not have sexual relations with that women,” Clinton said emphatically, although later he admitted that his definition of sex did not include getting a blow job, as their genitals had not made contact.

And then we come to Donald Trump. Perhaps no-one in modern history lies as glibly, easily, frequently and shamelessly as the current U.S. President.

The Washington Post has a fact-check team dedicated to the task of chronicling Trump’s mendacity, and since his inauguration on January 20 last year has recorded an astonishing 4,229 lies, half-truths, misrepresentations and exaggerations – at a rate of nearly eight a day.

Trump started his presidency with a lie, insisting his inauguration crowd was the biggest in history when actually it was dwarfed by Barack Obama’s.

On July 5 alone, Trump told 79 lies – either in speaking or via Twitter, his favorite medium – while June was his most productive month with some 532 lies in 30 days.

“I study liars and I’ve never seen one like President Trump,” wrote DePaulo in The Washington Post. “He tells far more lies, and far more cruel ones, than ordinary people do.

“By telling so many lies, and so many that are mean-spirited, Trump is violating some of the most fundamental norms of human social interaction and human decency. Many of the rest of us, in turn, have abandoned a norm of our own – we no longer give Trump the benefit of the doubt that we usually give so readily.”

If the bible was the origin of lying, perhaps Trump – and all of us – would be best served by reading from the Gospel of John, chapter 8, verse 32:

“The truth shall set you free.”