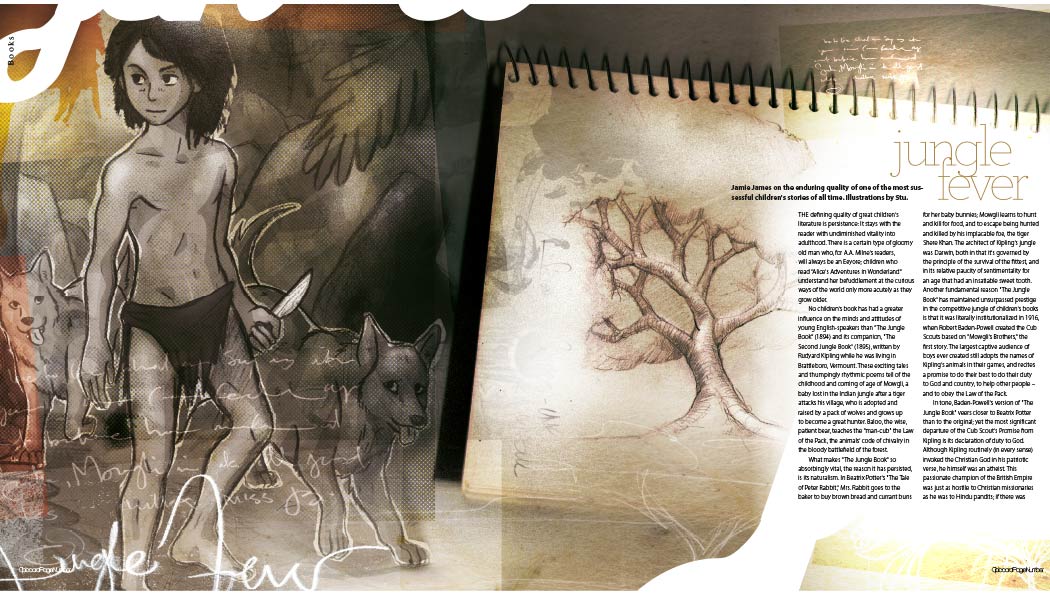

Jamie James on the enduring quality of one of the most successful children’s stories of all time. Illustrations by Stu (from The Yak Magazine Archive Issue 25, 2010).

The defining quality of great children’s literature is persistence: It stays with the reader with undiminished vitality into adulthood. There is a certain type of gloomy old man who, for A.A. Milne’s readers, will always be an Eeyore; children who read “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” understand her befuddlement at the curious ways of the world only more acutely as they grow older.

No children’s book has had a greater influence on the minds and attitudes of young English-speakers than “The Jungle Book” (1894) and its companion, “The Second Jungle Book” (1895), written by Rudyard Kipling while he was living in Brattleboro, Vermount. These exciting tales and thumpingly rhythmic poems tell of the childhood and coming of age of Mowgli, a baby lost in the Indian jungle after a tiger attacks his village, who is adopted and raised by a pack of wolves and grows up to become a great hunter. Baloo, the wise, patient bear, teaches the “man-cub” the Law of the Pack, the animals’ code of chivalry in the bloody battlefield of the forest.

What makes “The Jungle Book” so absorbingly vital, the reason it has persisted, is its naturalism. In Beatrix Potter’s “The Tale of Peter Rabbit,” Mrs. Rabbit goes to the baker to buy brown bread and currant buns for her baby bunnies; Mowgli learns to hunt and kill for food, and to escape being hunted and killed by his implacable foe, the tiger Shere Khan. The architect of Kipling’s jungle was Darwin, both in that it’s governed by the principle of the survival of the fittest, and in its relative paucity of sentimentality for an age that had an insatiable sweet tooth.Another fundamental reason “The Jungle Book” has maintained unsurpassed prestige in the competitive jungle of children’s books is that it was literally institutionalized in 1916, when Robert Baden-Powell created the Cub Scouts based on “Mowgli’s Brothers,” the first story. The largest captive audience of boys ever created still adopts the names of Kipling’s animals in their games, and recites a promise to do their best to do their duty to God and country, to help other people – and to obey the Law of the Pack.

In tone, Baden-Powell’s version of “The Jungle Book” veers closer to Beatrix Potter than to the original; yet the most significant departure of the Cub Scout’s Promise from Kipling is its declaration of duty to God. Although Kipling routinely (in every sense) invoked the Christian God in his patriotic verse, he himself was an atheist. This passionate champion of the British Empire was just as hostile to Christian missionaries as he was to Hindu pandits; if there was a religion he admired, it was Islam. In conversation, he habitually referred to the deity as Allah.

God plays no part in Kipling’s jungle; more crucially, neither does Empire, the principal theme of Kipling’s life and work. Writing about animals, ironically, enabled him to observe humanity (for the animals in the stories are plainly people) without the strictures of nationalism, which eventually strangled and embittered his thinking.

Written precisely on the cusp of the cinema era, “The Jungle Book” predicts that medium’s power to move and excite — a compliment returned in at least a dozen film versions. Events are narrated boldly, in a verbal equivalent of real time, and are often told from multiple points of view. Unencumbered by the need to proclaim the glory of Empire, “The Jungle Book” permitted Kipling to glory in pure storytelling, always his greatest gift. Henry James, an unlikely friend and defender, who once called him “the most complete man of genius” he had ever known, considered “The Jungle Book” to be Kipling’s finest work.

In no way does the rationalist-nationalist genius more closely resemble Darwin than in the scientific accuracy of his observations of wildlife. The best-known story in “The Jungle Book” is “Rikki-tikki-tavi,” one of the many non-Mowgli tales, about the doughty mongoose who does battle with Nag the cobra. Here, the snake makes his terrifying entrance:

“From the thick grass at the foot of the bush there came a low hiss — a horrid cold sound that made Rikki-tikki jump back two clear feet. Then inch by inch out of the grass rose up the head and spread hood of Nag, the big black cobra, and he was five feet long from tongue to tail. When he had lifted one-third of himself clear of the ground, he stayed balancing to and fro exactly as a dandelion-tuft balances in the wind, and he looked at Rikki-tikki with the wicked snake’s eyes that never change their expression, whatever the snake may be thinking of.”

Kipling not only conveys a vivid sense of danger and wickedness but also describes the appearance and defensive behaviour of Naja naja, the Indian cobra, with as precise an eye as any herpetologist. He saw just as clearly into the workings of a boy’s mind. (There are no girls in Kipling’s jungle.) Boys, he knew, like to be petted by their mothers so long as there are no other boys around to see it, but they understand that the playground is the real world. The cruelty of Mowgli’s code has been familiar to generations of children, who have instinctively felt the rightness of its central tenet: “The strength of the pack is the wolf, and the strength of the wolf is the pack.”

That first moment of reading a home truth that one already knows but has never seen put down in words is where the life of a reader begins.