Victor Mason chases the holy grail of blues in sixties America – and comes unstuck in the presence of its leading light.

It was late September or early October ’67, and I’d just quit my job in Hong Kong. I had it in mind to travel first to London, and from there to the good old US of A, first stop the Big Apple. Before emplaning at Heathrow a minor kerfuffle. I remember I was booked on Pan Am One and dutifully presented myself at their check-in counter. Sweet girl examined my British passport and said: “Oh, so sorry Mister Mason, but you don’t appear to have a visa.” Somewhat taken a back, I exclaimed: “Gosh! Do I need a visa to go to America?” “Well, I’m afraid you do. But don’t worry: we’ll help you to get one, and put you on a later flight.”

Pan Am van was summoned and sped me to the embassy in Grosvenor Square, accompanied by another sweet girl attired in a smart blue uniform. The place was packed: queues a mile long. I’d never seen so many miserable looking people. Sweet girl ushered me to the front of the queue and whispered something in an official ear. Five minutes later my passport was returned to me bearing a stamp which said – Multiple Entry Indefinite. We sped back to Heathrow. The entire operation had taken exactly one hour. Or it may have been one hour and ten minutes. Not bad going. I was in time to catch PanAm 2 whose ETD was two hours later than PanAm One.

Things are rather different now. The last time I flew to the States (which was not so very long ago), I was on a visa waiver and that meant I could stay in the U.S. for up to three months without one. I don’t think you can do that anymore. I was on my way to the Crescent City from London, port of entry being that hub of brotherly love – Philadelphia.

A slovenly overweight official kept us all waiting at the Immigration counter for an unconscionable age before finally condescending to put in an appearance. I was first in line. He cursorily examined my immigration form and passport, then, without saying a word, handed my documents to some uniformed flunkey behind him whom I was obliged to accompany to a room situated off the main concourse. Here another taciturn uniformed individual, without even looking at me, took over and started twiddling knobs behind a counter. When I reasonably enquired what might be the problem, I was summarily informed that it was none of my business and, furthermore, that if I didn’t stop talking I would be put on the next flight back to where I’d come from.

So what do you do? Tear the fellow off a strip, or clock him one for his confounded impertinence; demand to be taken to his leader; or simply hold your peace? Having decided on the latter course of action, I was eventually released into a maze of endless corridors, whence I finally managed to board my connecting flight with moments to spare. Well, what was the problem? My lack of visa; declaring Indonesian domicile (rather than British) on my immigration form; or hypersensitivity following 9/11? Combination of all three? We shall never know. But I do definitely digress.

It is 9/20 something/’67, and we are on our way to New York. The flight is practically empty: just a few other passengers: probably one of the new 707s, or it may have been a DC10: the cabin crew attend upon one’s every whim. Travelling by air I used to enjoy. Not any more.

Not having a clue where to stay, I took the advice of a very friendly cab-driver, who took me to a charming old bricken hotel situated near Grand Central Station. Delightful place if a bit dingy, though in the event I stayed there for only one night. I had the phone number of a chap I’d met in Hong Kong quite casually in some club: we’d had a few meals and a bit of fun together, and he had given me his business card and told me to give him a ring in the unlikely event (or so it seemed then) that I should ever find myself in the Big Apple. He answered my call immediately, told me to remain where I was, and said he would meet me at my hotel mid-morning. What luck!

Morty duly arrived at the appointed hour and, following the hail-fellow-well-met exchanges, I invited him to a celebratory libation at the basement bar. I remember with stultifying clarity that we had martinis – mine with olives, his with a twist. Only in America can you obtain a proper martini: don’t believe a word that pundits may utter to the contrary. Proper martinis must consist of the correct ingredients, and these do include a dash of dry vermouth. They should then be poured from a pitcher that has been kept in the freezer for minimum of twelve hours. They should also be served with a side-dish of pretzels, oysters, or cherry-stone clams. In any establishment worthy of the name, you shouldn’t have to ask for these.

I can still hear to this day Morty’s exhortation over the second of these divine concoctions. “You gotta get outa this dump. I have just the place for you. Trust me.”

It didn’t take me long to bundle up my meagre accoutrements and pay the bill, which amounted to precisely, sixty dollars, cost of martinis inclusive. Fantastic value! Less costly than you’ll find in most other old or New World cities. His spanking motor – a not-so-shiny black Dodge – stood directly without the hotel’s front entrance, under the attentive eye of a liveried footman, who it seemed was familiar with my host. We roared down Park Avenue, or it may have been Broadway, and presently found ourselves at the heart of Greenwich Village, on the corner of Bleecker and Grove Streets. I recall the location well, for it was to be my home for the coming fortnight at least. The ground floor apartment was extremely snug if not very spacious – about the same size as my recently vacated hotel room. It belonged to my friend, though he seldom used it, preferring to stay with a lady companion who shared a swankier space somewhere near Central Park.

“Here,” said Morty, handing me the keys, “it’s all yours. Just don’t forget to double lock the joint. Do anything you like in it, only try not to burn the place down!” Before speeding away he said he’d pop by in a day or two to see if I was settled in OK.

So here we are, superbly established in the Village, where all the action is; and (remember the Blues Brothers?) I’m on a mission, a musical mission… Practically the first thing I did was to find a record store – it was all vinyl then – and there, pasted on the window, was a poster advertising the Muddy Waters Blues Band who were playing at a newly opened venue styled the Electric Circus, which happened to be not a million miles unadjacent and a ten minutes’ cab-ride away.

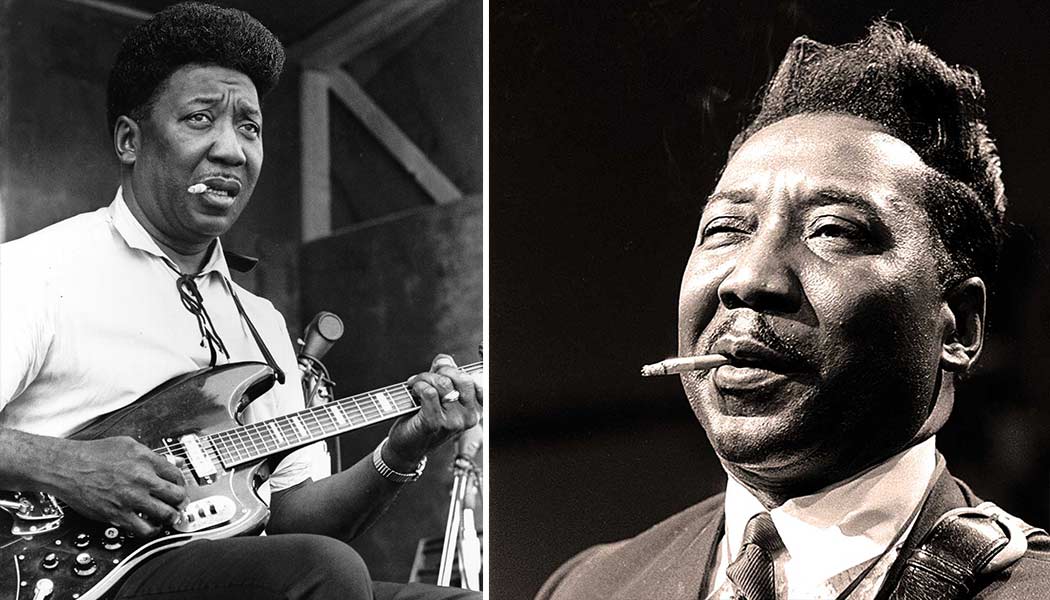

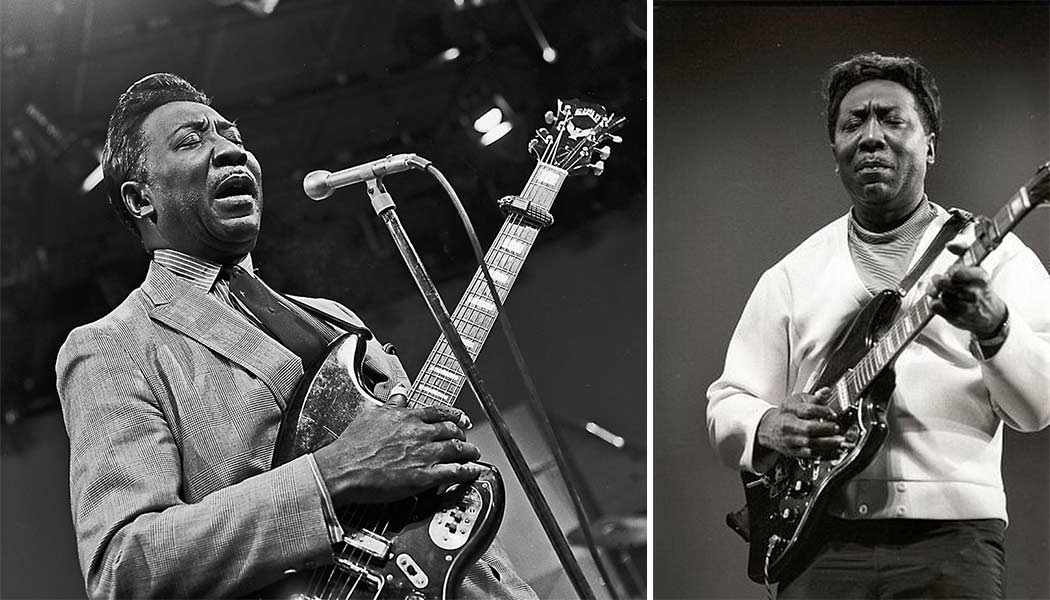

Muddy Waters. Definitely up there in my Blues Pantheon: I had several of his records, including under his real name – McKinley Morganfield – those seminal early Forties Library of Congress tracks issued on Testament, and some marvellous Fifties Chess albums, with Little Walter on harp. Gotta hear this guy in the flesh. Say no more!

I’m under the impression that the man behind the Electric Circus was Bill Graham, who founded the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco. It was known for a while as the Fillmore East if I am not mistaken. Tricked out like a big top, the cavernous interior was circumscribed by a foam banquette, convenient to collapse upon. But it was the sound, the stupendous wall of sound, that I recall most vividly. Muddy and his men occupied the centre of the arena: there were three or four guitars, harp, keyboard and percussion, and the music they played simply blew you away, bowled you over, swept you off your feet, knocked you out, transubstantiated you. It was pulverizing. Nothing on vinyl could capture it.

Now it just so happened that I had an introduction to Muddy’s manager, Bob Messinger, who had also handled the Ken Colyer band in London. I sought him out and asked if he would kindly allow me to interview the maestro himself. “Sure, why not?” said the good man, “I’ll send you word.” And presently I was conducted to what looked like a disused lift well somewhere in the back of the building, where the looming presence awaited me. One needs to get things in perspective. Here am I, all alone with one of the greatest blues artists of all time. It is only my second night in the New World, in the Big Apple, in at the deep end so to speak. One of the greatest blues artists of all time eyed me somewhat quizzically.

“Mr Morganfield I presume” was my opening gambit; and the great man nodded and smiled lopsidedly. “Hey, hey, whadaya know?” I said I knew because I had his very first recordings. “So?” “So wherefore the name Muddy Waters?” That lopsided smile again, and a shrug. Obviously he didn’t want to talk about it. In fact, I reflected later, he’d probably been asked the same question 1001 times; in any case I knew wherefore, because blues writer, Paul Oliver, had written about his upbringing on the family farm in Mississippi, where he used to spend his days mucking about in the local creek. I then asked him how he found his current harp player, George Buford, who it seemed to me was every bit as good as Little Walter. Silly question, I suppose. “OK,” was all he would say. And the rest of the band? And his present gig? And what the future might hold? He was totally unresponsive. Dammit! He was looking at his watch. Time for the next set. I suggested that he join me for a drink at the bar when he’d finished playing. “You do drink, don’t you?” Not even a nod. He wandered off, and that was that.

Back in the big top, I was accosted by guitarist Mike Bloomfield, who just happened to be there, and who’d recently split from the Butterfield Blues Band to form his own outfit – the Electric Flag. “Whadaya mean asking Muddy all those damn fool questions?” he raved at me. “What questions?” “Like ‘do you drink?’ and shit like that!” I’d had enough. I turned on my heel and headed for the bar. But worse was to come. Far worse. And this time I deserved to be on the receiving end.

But a few doors away from my digs was a bar. A fabulous bar, which I’m pretty sure was called the Bleecker Street Bar. Here was I wont to repair around midday for my first martini – simply the best martini in town, ergo the world. Served with pearl onions and endless dishes of cherry-stone clams, I could happily have stayed there all afternoon, rhapsodizing about the American Dream, Blues and Jazz, and the Status Quo. A couple of days or so following the Bloomfield rebuff, I was there, appraising the clarity and molecular structure of the divine admixture before me, when this chap plonks himself down beside me. “Wow, that looks good! I’ll have one of those,” says he.

An animated conversation ensued, doubtless inspired by an endless succession of crispy, cocktails and succulent clams. And I may have been shooting a bit of a line, waxing ever more garrulous and beset by delusions of grandeur. There is no doubt that the devil got into me. My new-found companion evidently knew nothing of the Blues, so I took it upon myself to enlighten him.

The taxi delivered us St Mark’s Place and the Electric Circus as Muddy was beginning the first set. I recall vaguely charging past the orderly box office file and bouncers, gesticulating and name-dropping wildly; starry-eyed, stumbling acquaintance in tow. Then the wall of sound hit me; keeling over to a cushioned collision, I knew no more.

When I came to, it was eerily silent. It seemed that I was alone in that vast hall, though I suddenly became aware of the figure standing directly over me. The voice sounded more aggrieved than incensed. “What on earth did you do that for?” It was Bob Messinger. “Christ!” I mumbled, “I’m so sorry; I think I must have passed out. Did I miss the whole show?” “Never mind that. You came in here without paying, you prick. You just can’t do that. Do you know how much it costs me to run this group? I’ve gotta look after them, pay them, feed them, cloth them …” And more in similar vein. “Look, I’m really sorry,” I said: “I didn’t mean it. I guess I got carried away. Please take this.” Handing him a wad of bills and tendering more abject apologies, I took my leave. In the event, I felt truly contrite. It was a dreadful thing I had done. But the realization that I had slept through three whole sets by Muddy Waters and his Chicago Blues Band was the most chastening of all.