“One crowded hour of glorious life is worth an age without a name,” wrote Sir Walter Scott. Andrew E. Hall looks at what it takes to be a real hero. Pay attention kids.

Fly like a butterfly .. sting like a bee.

WHEN you hear the words “hero” or “heroine”, who comes to mind?

Maestro, some think, music please …

In the meantime let’s do a quantum leap back to the ancient world – Greece would be a good stopover; a place that spawned the etymology of “hero”.

The original word derived from the ancient Greek for a demigod cult in which supra-human figures dominated the religioscape – entities worthy of various forms of worship (who either scared the hell out of, or promised some kind of fulfilment and/or utility to, worshippers).

Achillies … the Greeks pretty much invented the concept of heroism.

The term evolved over time to encompass individuals who, against the odds, overcame dire circumstances and personal disadvantage to achieve “victory” – more often than not for some greater good and/or the protection of larger numbers of lesser mortals.

Homer’s Iliad is, arguably, the text that got the hero thing up and running with its gripping account of the Trojan War and its aftermath. I’m sure someone has researched the taxonomy of terms in Homer’s epic poems that are still used widely today.

Before stilettos there were heels … Achillies’s weak point.

“Trojan horse”, for instance, is a current vernacular for particularly nasty viruses implanted by particularly nasty people in our computers; “Achilles heel” is a term for weakness or vulnerability because the great warrior got shot in the foot with an (some say poisoned) arrow fired by a chap named Paris (who later got his own city); our term “odyssey” comes from Odysseus who took 10 years to get home to Ithaca from Troy – whereupon he slaughtered all the men who’d tried to boink his wife, Penelope, during his absence. And on and on; there’s heaps of them.

The philosopher, Socrates, said: “Fame is the perfume of heroic acts”, which lends another aspect and perspective to the rationale for carrying them out.

So what does it mean today when people are referred to as heroes or heroines? Who are these people, and what does it mean to be “heroic” in contemporary parlance?

A TALE OF TWO WARS – Neil Davis and friends:

War correspondent Neil Davis

The lines of the stanza that leads this piece were inscribed at the beginning of every workbook owned by Neil Davis – an Australian combat cameraman who left school aged 14 to work in the Tasmanian Government Film Unit.

In 1964, aged 30, he travelled to Borneo to cover the Konfrontasi between Indonesia and Malaysia. And was soon thereafter to find himself in Vietnam and Laos covering what was to become known as the Vietnam War for media company Visnews.

In those days there was no such thing as being “embedded” with assigned military units, which is a common feature of war reporting today. Correspondents, then, went where they chose (which usually meant the front line) by whatever means at their disposal.

Davis’ desire was to get up close and personal with war and to portray the effects it had on the individuals fighting it – which meant, often, capturing their last moments of life. He was uncommon in the sense that he chose to carry out his assignments with the South Vietnamese troops in battle, as opposed to the usual practise of following the Americans around. He always worked alone – choosing not to put others’ lives at risk.

His footage was stark and brutal.

I remember seeing a film he made called The Hand-Grenade Thrower, which depicted a close-quarter battle in which a South Vietnamese soldier broke cover again and again to lob his ordinance at the enemy. Davis filmed his dying moments as the mortally wounded man looked at us, the viewers, with an expression that congealed determination and confusion – stitched up by machine gun fire.

Neil Davis front and centre in Vietnam.

Davis was seriously wounded on a number of occasions, and on one of them a transfusion from a coconut probably saved his life.

Neil Davis had colleagues during that war – notably (Welshman) Philip Jones-Griffiths and (Dutchman) Hugh van Es, whom I had the pleasure of meeting on a number of occasions during their visits to Bali in the late 1990s and early 2000s. They were both combat photographers – referred to by the term “shooters”.

Hugh van Es.

They said Neil Davis was an unreconstructed cadger of other people’s cigarettes.

It’s ironic that in the midst of a dirty and devastating war that the men and women armed only with cameras should be called the shooters.

Hugh is best known for his photograph of the last CIA “Air America” helicopter to leave Saigon, shortly before the fall of that city to the North Vietnamese in 1975. But his work for UPI and AP took him into many a battle zone, including the May 1969 Battle for Hamburger Hill (depicted in the Hollywood film of the same name) in the A Shau valley.

Viet evacuation by Hugh van Es.

Popular myth would have it that the last chopper out was lifting from the US embassy in Saigon – the reality is that it was actually leaving from the Pittman Apartments building across the road from the UPI bureau office, as Hugh wrote in The New York Times in 2005:

It was Tuesday, April 29 1975. Rumours about the final evacuation of Saigon has been rife for weeks, with thousands of people … being loaded on transport planes at Tan Son Nhut airbase to be flown to US airbases on Guam.

… I had decided, along with several colleagues at United Press International, to stay as long as possible … (O)n the way back from the evacuation point (on Gai Long Street), where I had gotten some great shots of a marine confronting a Vietnamese mother and her little boy, I photographed many panicking Vietnamese in the streets burning papers that could identify them as having had ties to the United States.

Hugh returned to the UPI office to restock and reload.

… (A)round 2:30 in the afternoon, while I was working in the darkroom, I suddenly heard Bert Okuley shout, “Van Es get out here, there’s a chopper on that roof.”

I grabbed my camera and the longest lens in the office … and dashed to the balcony. Looking at the Pittman Apartments I could see 20 or 30 people on the roof, climbing a ladder to an Air America Huey helicopter. At the top of the ladder stood an American in civilian clothes, pulling people up and shoving them inside …

Hugh earned US$150 for the image – despite it being used thousands of times as a symbol of that war.

Philip Jones-Griffiths was as loquacious and passionate a man as I ever met – passionately anti-war, passionately socialist. His images of Vietnam were wired around the world and, in keeping with Neil Davis’ and Hugh van Es’s, were confronting, controversial, and concentrated on bringing attention to the suffering of the Vietnamese people.

Philip Jones-Griffiths.

Working for the Magnum company, he found the images hard to sell … until he had a stroke of luck and photographed Jackie Kennedy (wife of former US president John F. Kennedy) holidaying with a male friend in, of all places, Cambodia.

Those images earned him enough to publish a book titled Vietnam Inc. in 1971. Much to the chagrin of the US body politic, the book had a major effect on civil America’s perceptions of the war … not a good one.

Philip also earned an honourable mention from South Vietnamese president, Nguyen Van Thieu: “Let me tell you there are many people I don’t want back in my country, but I can assure you mister Griffiths’ name is at the top of the list.”

Not bad for someone who grew up as a working class Welsh lad.

The pain of war, Vietnam, by Hugh van Es.

On April 30th 1975, Neil Davis (having resigned from Visnews and working as a freelancer) filmed the first North Vietnamese tank breaking through the gates of the presidential palace in Saigon – an image that became an enduring symbol of America’s ultimate defeat in the war.

1975, Saigon, Neil Davis.

Davis later said: “I knew if I managed to survive the first minute or two I’d be alright.”

Not that any of these three would for a moment wish to be regarded as heroes, what they did was courageous and (self-) life-threatening. Each had a burning desire to portray the senseless insensitivity of war to a public that might, just, be shamed enough to call for it to be stopped.

In many respects they were successful.

Neil Davis was killed by tank-shell shrapnel, covering a shitty little coup in Bangkok in 1985. His life is commemorated in the book, One Crowded Hour, by Tim Bowden.

Hugh van Es told me that all who attended Davis’ funeral threw cigarettes into his grave.

Sadly, Hugh and Philip have also moved on.

Hugh van Es.

A TALE OF TWO WARS – The Boys from Baghdad:

During the run-up to Gulf War 1.0, in 1991, correspondents from CNN (sometimes known as Chicken Noodle News), Peter Arnett, Bernard Shaw, John Holliman, and their techie crews (Richard Roth turned up as well) set up their stuff in the Al-Rashid Hotel in Baghdad, Iraq.

The Iraqis had invaded Kuwait and nobody was happy that a western-friendly Gulf Nation’s resources were being threatened by some vainglorious loony (Saddam Hussein).

It was potentially great TV though.

Journalists and correspondents from other media outlets were also there, including one who wrote for The South China Morning Post – British journalist, Bruce Cheesman, who, not long after that conflict had been resolved, did me a favour by giving a guest lecture for journalism students in the university I used to work at.

The CNN “Boys from Baghdad” had a lot of communications gear and – unlike in the conflict previously alluded to – they were not willing to share it … it’s a petty competition thing. So, 10 days after the allied bombing of Iraq had begun – for which the Boys from Baghdad received many plaudits (mainly from CNN) for filming and commentating upon the extravagant light and death show (laid on by the US Navy and US and British Air Forces) from their balcony at the Al-Rashid – the only way Bruce could file his copy was to find an outside telephone or fax.

Trying to find his way through the rubble-strewn streets he was kidnaped by Iraqi government types, blindfolded, and thrown into the boot of a car. He was shunted from pillar to post for more than five days and interrogated on suspicions he was a spy.

He said he was afraid for his life. I believed him.

When he was finally dumped back in front of the Al-Rashid (his personal and journalistic credentials, which he had carried with him were, finally, taken to be legitimate), shit-scared, disheveled and hungry, he managed to find a phone to call his parents.

He asked the Boys from Baghdad for sustenance – maybe a drink of something strong.

They had stores.

They refused.

Bruce was still quite angry when I met him.

Any heroes here?

Perhaps the Boys from Baghdad had smelt Socrates’ perfume … from having their heads stuck firmly up their own arses … or as Albert Einstein once quipped: “Heroism on command, senseless violence, and all the loathsome nonsense that goes by the name of patriotism – how passionately I hate them!”

POPULAR CULTURE (as if the mainstream media aren’t PC enough):

Superman is not dead.

Superman never made any money

For saving the world from Solomon Grundy

And sometimes I despair the world will never see

Another man like him

– Crash Test Dummies

Load of old cobblers, of course he made money – poncing about as reporter for the Daily Planet, Clark Kent. What were those Canadians thinking?

Think about it – Superman – he’s faster than a speeding bullet (fairly quick); stronger than a locomotive; bulletproof; pretty much indestructible by any other means (except if you’ve got a bit of kryptonite in your pocket); and … he can fly … into space if necessary!

What’s so heroic about the fact he can beat the crap out of the bad guys? The boy holds all the cards. Fair enough, he has a conflicted love interest … haven’t we all?

Nuff said for him and the pantyhose-clad noddies who try to emulate him.

WHAT’S UP WITH US?

Having disparaged the comic book hero of millions, I’ll try to redeem myself somewhat by posing a question: are there any similarities between Superman, Spiderman and, say, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.?

Obviously the relative dress codes aren’t a factor, nor the fact that two of them are figments of fertile imaginations. I would suggest, however, that there is, indeed, a common linkage – that of morality.

While our two corporeal candidates struggled over many years to achieve appropriate recognition and justice for their people – in Gandhi’s case, people of colour in South Africa, and Indians in India; in King’s, African Americans. Our two fictitious characters also represent a moral dimension, a protective penchant for those who are oppressed by those who are stronger and less inclined to clemency. More to cruelty.

Rosa Parks, activist for black America.

Rosa Parks was an African American woman (died in 2005) who became a heroine to many simply because she refused to give up her seat on a bus in 1955 to a white man.

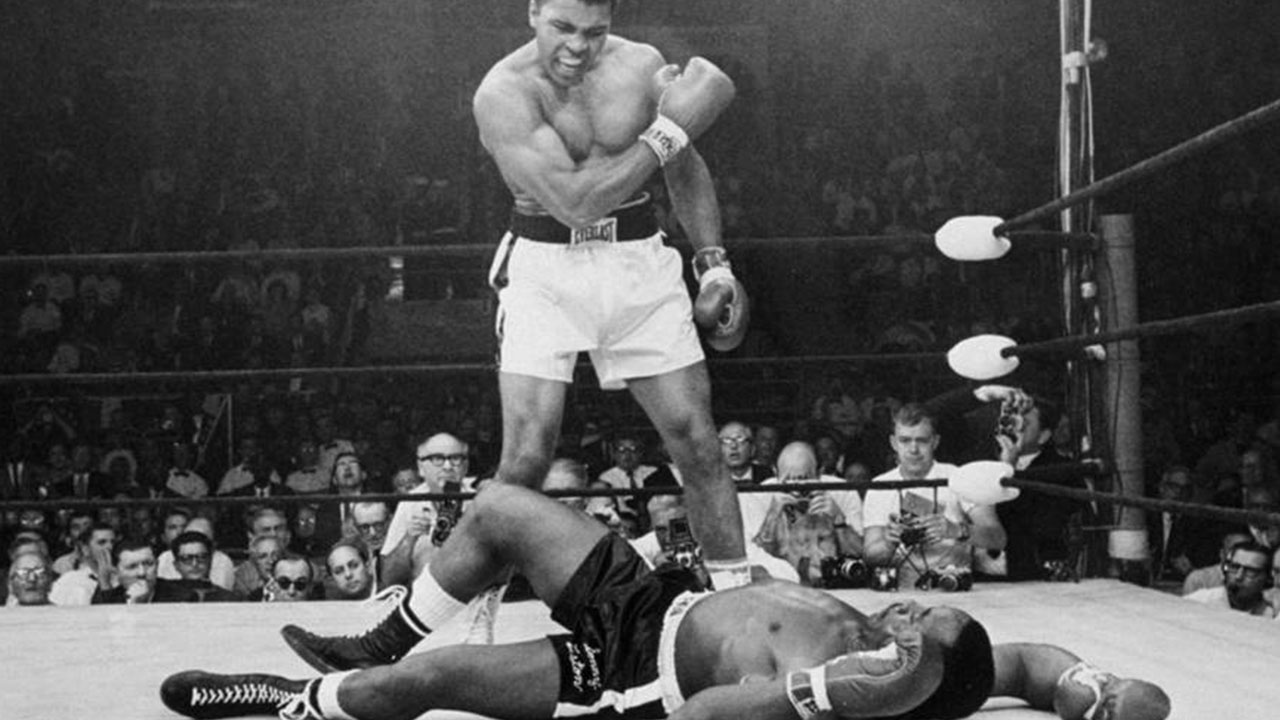

She had no political cachet, no silly suit. She merely insisted that she had as much right to a bus seat as any white man, or woman. For this she was arrested! But her action had a momentous effect in the US civil rights movement …… as did the actions of the greatest boxer who has ever lived, Mohammad Ali, who floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee.

Born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. in 1942 in Louisville, Kentucky, he changed his name in 1964 after discovering the Islamic faith and joining the Nation of Islam, which was presided over by civil rights campaigner, Malcolm X.

Ali.

Ali’s boxing career stretched from the late 1950s to 1981 – he won Olympic gold at the Atlanta games in 1960 and the world heavyweight championship three times. He was referred to (respectively and respectfully) as The Greatest, The Champ, and the Louisville Lip – because of his penchant for provocative patter. He once summed up his art in this way:

“Boxing is a lot of white men watching two black men beat each other up.”

Ali became a hero to millions because of his exploits in the ring. He became a hero to millions more because of his unflinching commitment to social justice.

“I know I got it made while the masses of black people are catchin’ hell, but as long as they ain’t free, I ain’t free.”

In 1967 Ali refused to be drafted into the US Army, declaring himself a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. He explained himself thus:

“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong … They never called me nigger.”

And …

“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?”

“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong … They never called me nigger.”

For this stance Ali was stripped of his heavyweight title, had his boxing license rescinded and was arrested and convicted of a felony – for refusing to step forward when his name was called for the draft. Ali spent four years in the boxing wilderness – many say his potentially most potent years – appealing his conviction and making what money he could in public speaking engagements.

“Wars of nations are fought to change maps. But wars of poverty are fought to map change.”

Ali’s 1967 conviction was finally overturned by the US Supreme court in 1971; his boxing license was returned and he went on to regain the heavyweight championship in 1974 in a fight hyped as “The Rumble in the Jungle” against George Foreman.

In his retirement, and despite being afflicted by Parkinson’s syndrome, Mohammad Ali still traveled the world as an ambassador for peace and human rights.

He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Honor in 2005.

*****

Here are three more heroic examples (according to some):

Joseph Stalin and Mao Tze Dung – heroes of communism; and Adolph Hitler – hero of the so-called Aryan races. Between them they racked up a body count that is staggering in its obscenity … regardless of what conspiracy theorists purport.

Crawl back under your rocks.

Yet there are still people – lots of them – who lionize these murderers.

There are still people who march in the UK and Europe and America under the aegis of the nazi (lower case intentional) swastika. And let’s clear something up here because I’ve been asked many times recently why the swastika is such a common symbol on Bali: the Hindu swastika is an ancient symbol of the sun and, as such, is a bringer of life; the nazi swastika was appropriated from the Hindus, reversed in its direction and used as a political prop and a perverted shadow of death.

What bamboozles me is that, particularly in America, the Aryan (nazi) movement is made up, largely, of fundamentalist Christians. And other (prominent) fundamentalist Christians in that country would rather devote their energies to promoting the idea that Barack Obama is a Muslim than distancing themselves from these craven crazies.

God moves in mysterious ways …

Santa Clara University ethics scholar Scott LaBarge writes: “We need heroes because they define the limits of our aspirations … we define our ideals by the heroes we choose, and in turn, our ideals (courage and honor, for example) define us.

Donald Trump not pictured.

Heroes symbolize the qualities we’d like to possess and the ambitions we’d like to satisfy. For instance, a person who chooses women’s rights crusader Susan B. Anthony as a hero will have a very different sense of what human excellence involves than someone who chooses, say, a contestant on a reality TV show.”

WEALTH AND POWER:

Just when I thought I’d almost finished this piece and all that was left was to come to some cogent conclusion, along came the prodigious shadow of Rupert Murdoch and the scandal that led to the closure of his British tabloid newspaper, the News of the World.

Thanks Rupe!

Long story short: journalistic and senior management staff on that newspaper (which many would regard as a worthless rag except, in a quirk that defies comprehension, many other working journalists around the world) have had criminal charges laid against them for hacking into more than 4,000 people’s private communications devices. Including that of a murdered teenager.

The scandal claimed the positions of two of the UK’s most senior policemen (because it has been alleged that police officers were being bribed by the paper to reveal people’s private information); the jobs of more than 200 people who worked for the News of the World; the life of the original whistleblower – a former reporter on the paper by suicide, drug overdose, or some other means several days after the story broke; and, at the time of writing, had wiped around a billion dollars off the Murdoch family fortune – astoundingly this is not much of an ouchie, more a blow to the ego.

The reputation of the Prime Minister of England was called into question because he, along with many, many, other political leaders throughout the world have kowtowed to Murdoch’s media might for many, many years.

John Emerich Edward Dalberg Acton, first Baron Acton (1834–1902) coined the phrase:

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely …”

Rupert Murdoch is chairman and CEO (at the time of writing) of News Corporation and it’s News affiliates around the globe. He owns more than 40 percent of Britain’s newspapers and a controlling interest in that country’s largest satellite broadcaster, BSkyB; the Fox network and many newspapers in the US including The Wall Street

Journal and The New York Post; more than 70 per cent of Australian newpapers. And that’s just some of it!

Can you imagine how much influence he has on opinion broking?

It’s frightening.

He had the audacity to swagger into London during the third week of July that year claiming that the whole fracas was a load of nonsense and a beat-up. He treated people with his customary contempt and lamented the fact that he was being misrepresented in the press (that which isn’t owned by him, at least). His News outlets, in the main, continued to lead with stories of David Beckham’s prodigious intellect and Posh Spice’s tits.

Murdoch’s attitude remained dismissive.

“Our competitors are creating this hysteria …” he reckoned.

Until, that is, he and his heir-apparent son, James, and the (recently) former CEO of News’ UK arm, News International, Rebekah Brooks, were dragged before a UK Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry.

“This is the most humble day of my life,” he said.

He’d hired the most prominent PR “crisis” company in the land … and that’s all they could come up with.

Along with endless repetitions of “I’m sorry”.

In a 2009 posting on the “Heroes of Capitalism” blog Murdoch was characterized thus:

“Regardless of your opinion about his tactics, it is clear that Rupert Murdoch has built a tremendous amount of wealth for himself and for the tens of thousands of employees he has working for him worldwide. And this makes him a Hero of Capitalism.”

Go figure.

… and watch your news space – best if it isn’t owned by the repentant octogenarian – for what promises to be a lengthy, and very dirty, fight.

Again, it’s all about choices. Unfortunately, these days, there appears to be a general consensus that the mere fact that someone is wealthy is reason enough to imbue him or her with heroic attributes. Regardless of what kind of mean and sneaky person they might actually be.

Of course there are rich folk out there who use their resources for the good the larger world community. Ted Turner is one of them. Bill and Melinda Gates might even fit into this category.

MOUNTAINS TO CLIMB:

Sir Edmund Hillary and sherpa Tenzing Norgay.

As for the rest of us, I’m happy to put my faith in people like Sir Edmund Hillary who is an heroic figure, not simply because he (with his Sherpa guide) was the first man known have summited Mount Everest, but because he spent the rest of his life building schools and hospitals in the Himalayas.

Sir Ed said: “You don’t have to be a fantastic hero to do certain things – to compete. You can be just an ordinary chap, sufficiently motivated to reach challenging goals.”