Cuba’s sultry seafront capital belongs to the romantic past, writes Joe Yogerst. Photography D.Hump.

“Playing the violin is a lot like courting a beautiful woman,” says Fernando Ortega as he slips into the opening strains of a traditional Cuban love song. “It’s got to come from the heart. Otherwise the act is meaningless.”

It seems an incredibly old-fashioned declaration, completely out of step with the, often, harsh pragmatism of the modern world. But then again you’ve got to consider the location. Fernando’s place of work, where he gently caresses the horsehair strings each evening, is a candle-lit restaurant overlooking the Havana waterfront.

In nearly every respect, Cuba’s sultry seafront capital (the Caribbean region’s largest city with 2.2 million people) harks back to a different time. Not just the hackneyed Havana of the 1950s, but a dozen different ages spread across 500 years of urban history.

You can mount the bastions of Castillo del Morro, the huge coral-stone fortress that guards the entrance to Havana Bay, and gaze down on waters that once harbored treasure-laden galleons en route from Mexico to Mother Spain, their holds packed with silver, gold and other New World riches.

You can stroll through the leafy Plaza de Armas and hear nothing but the sound of your own footsteps and the clippity-clop of a horse-drawn carriage making its way down a cobblestone street, an experience that instantly transports you back to the 19th century when Havana was governed by wealthy and erudite Spanish elite.

You can lounge away an afternoon on the terrace of an art-deco gem called the Hotel Nacional – while the house band plays a geriatric rumba – and pretend that it’s suddenly Prohibition again and those conspiratorial fellows smoking stogies and sipping mojitos at the adjacent table are none other than mobsters Al Capone and Meyer Lansky (both of whom frequented the Nacional during the 1930s).

Or you can slip into silk jacket and Panama hat for a midnight time trip back to the 1950s at the city’s celebrated Tropicana, a sprawling outdoor nightclub that features Latin big band sounds and some of the most exquisite creatures in Cuba prancing around in little more than feathers and sequins.

“Our man in Havana belongs – you might say – to the Kipling age,” wrote Graham Greene in 1958. “Walking with kings and keeping your virtue, crowds and the common touch.” And it’s still that way. Well, maybe not keeping your virtue. The Cuban capital has enough vices to keep purgatory burning busy until the end of time. But Greene’s overall thrust still holds true: Havana is a city that savours, almost worships, the past.

More than anything else, the cacharros (jalopies) reflect the city’s time-warp ambience. Despite a recent influx of European and Japanese vehicles, classic American cars continue to rule the capital’s streets and Cuban highways in general. Often packed with a dozen or more passengers, these four-wheeled anachronisms – big fins and bumpers gleaming in the tropical sun – provide an essential service in a country that’s always been chronically short on public transport.

Packards, DeSotos, Chevy Bel Airs, Buick Centuries – spend enough time in Havana and you’re likely to spot just about every 50s make and model. It’s a wonder how they remain roadworthy after all this time.

“We’re cannibals,” says Ricardo Cuevas, who pilots a vintage Oldsmobile 88 for a taxi service.

“Cacharro owners are always hunting for other cars to scavenge parts, especially for the engine. And all of us, we are excellent mechanics.”

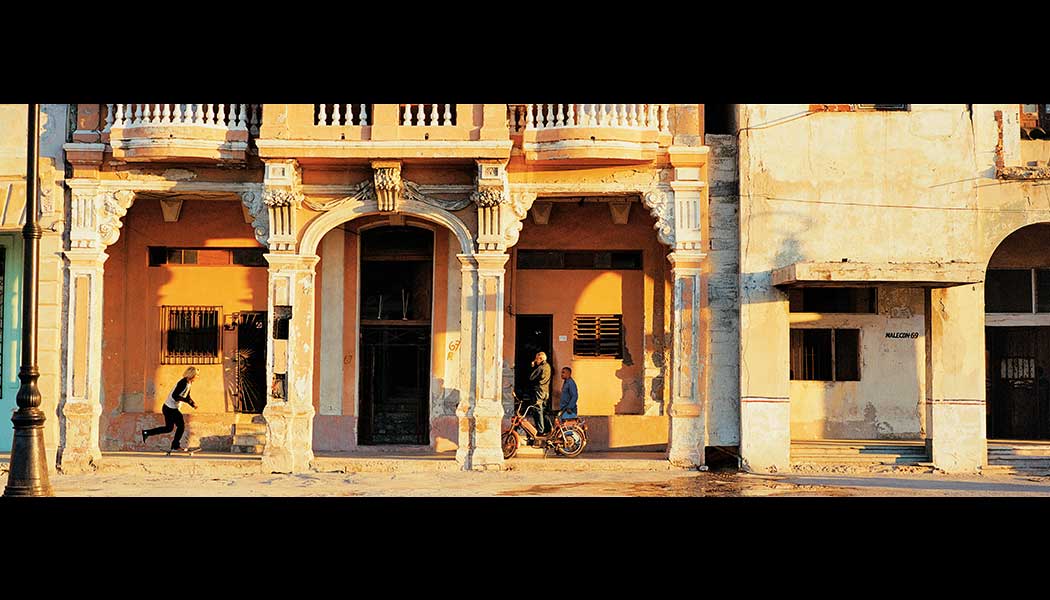

But Havana isn’t just old cars. It’s also a haven for old buildings. The city boasts the greatest wealth of Spanish colonial architecture in the western hemisphere – a treasure – trove of churches, palaces, citadels and mansions wedged along narrow streets or looming over palm-fringed plazas. The vast majority of these bygone beauties are found in Habana Vieja (Old Havana), which roughly covers the area of the original Spanish settlement. But newer neighborhoods like Habana Centro and Miramar also boast their fair share of faded queens.

With assistance from UNESCO (which named Old Havana a World Heritage Site in 1982) and other international organizations, Cuba’s National Center for Conservation, Restoration and Museums has identified more than 900 structures of historic importance. Much of the revenue from hotels, restaurants and galleries in the old town is plowed into restoration efforts, an ongoing effort that will take decades to complete.

Although much of the more recent renovation concerned buildings along the Malecon waterfront of Habana Centro, the initial phase focused on the old town’s most important squares. The ancient and venerable Plaza de Armas dates from 1519, when the city was founded by Diego Columbus – son of the famous explorer. The plaza is surrounded by incredible colonial buildings, including the wonderfully restored Palacio del Conde de Santovenia (now the posh Hotel Santa Isabel) and the hulking Palacio de los Capitanes Generales where the Spanish governors once reigned.

During the week, the plaza remains quiet as a church mouse. But on weekends, the cobblestone quad transforms into a much different creature – an outdoor antique book market and an impromptu venue for the city’s best buskers. Covent Garden come to the Caribbean. You never know what you’re going to find on any given day: Salsa, circus or even classic ballet. And if your feet fatigue, retire to one of the sidewalk cafes on the plaza’s southern flank where ice-cold beer is always close at hand.

Footsteps away is the even more spectacular Plaza de la Catedral, a cobblestone masterpiece framed by Italian renaissance-style palaces and the imposing baroque facade of San Cristobal Cathedral (completed in 1777) where the elder Columbus was once buried. Another open space flanked by wonderfully restored colonial structures is the Parque Cespedes (or Tacon) along the old town waterfront, another venue for outdoor cafes and a daily art market that features many of the city’s best young painters.

Another local trademark is the jinitero or hustler. The literal translation of this Spanish term is someone who rides, like a cowboy or cyclist. But in Cuban slang it refers to someone who “rides” a tourist or foreign visitor for money or favors. You can’t stroll across Parque Central in the old town or amble down La Rampa avenue in the bustling Vedado district without hearing their eager chorus: “Wanna buy cigars? Need a place to stay? Looking for some company?”

Their whispered promises are a direct link to the city’s black market or bolsa – a vast underground economy that operates outside of state control. Depending on your particular needs, street hustlers can be a huge help or a minor nuisance.

But even if you don’t employ their service, jiniteros are always game for a little friendly conversation. “How can you call it the World Series?” asks a hustler perched on a wall outside the Hotel Ambos Mundos, where Ernest Hemmingway once lived and wrote. He’s talking about baseball, of course, one of the abiding passions of local life. “Some American teams – they’ve got Cuban players. Good ones, too. Incredible! But without a team from Havana it can never be a world series. Don’t you think?”

One way to beat the touts is ducking into one of the city’s superb museums. The Caribbean is known for fine sand rather than fine art. But Havana is a startling exception, a holdover from Spanish colonial days when Habaneros considered themselves the most refined urbanites in all of the Americas. A leafy boulevard called the Prado – created in the 19th century as a scaled-down version of the Champs-Elysees – has evolved into the city’s unofficial museum row.

The Museum of the Revolution – housed in the former Presidential Palace – details more than a hundred years of Cuban struggle against both foreign and domestic oppression. An entire room is given over to the memory of legendary guerrilla leader Che Guevara, often hailed as the supreme martyr of the Cuban Revolution. In the museum gift shop, tourists clamor for T-shirts, key chains and postcards bearing his bearded, long-haired likeness. But you really have to wonder what Che himself would have thought of all this – transforming his radical image into a capitalistic cash cow.

Looming directly behind the rebel shrine is Cuba’s National Museum of Fine Art, which reopened in the summer of 2001 after a three-year renovation. Without doubt, this is now one of Latin America’s finest art collections. The modern wing houses a treasure trove of homegrown art, from the cubist masterpieces of Wilfredo Lam (a Picasso pupil) to the revolutionary pop art of Raul Martinez who surely must have drawn his inspiration from Andy Warhol.

The museum’s international collection, housed farther up the Prado in a meticulously restored Belle Epoque palace, includes many works that were left behind by Cubans fleeing the revolution or expropriated from wealthy families after Castro came to power – the first time that such items have been displayed in public.

“Art” of a much different sort is on display at the Fabrica de Ron Bocoy, the city’s most important rum producer. Some of Cuba’s finest libation is produced within its hundred-year-old walls.

“Cuba is famous for three things,” says distillery guide Yemsis Cardoso as he leads a group of visitors on a factory tour.

“The world’s most beautiful women . . . the world’s best cigars . . . and the world’s finest rum.”

Cardoso leads the way down narrow wooden stairs into the bowels of the building, where the precious liquid is aged in huge oak barrels.

“We produce four types of Cuban rum,” he explains. “Carta blanca is aged three years, Carta Oro is aged five years and Anejo is aged seven years,” he says.

He hesitates a moment, his lips twitching, waiting for someone to ask about the fourth variety. And when someone finally does, he breaks into a wide grin.

“Isla del Tesoro (Treasure Island) — which is aged more than a dozen years and available only to guests of Fidel Castro. So unless you are having cocktails with our president tonight, I am sorry to announce that you will not be able to sample it.”

You don’t have to be a world leader to savor another of Havana’s eternal pleasures: Cuban music. Song is everywhere – on the streets, on rooftops, in people’s homes and on their lips – most of it homegrown, born and bred on this largest of Caribbean islands, synthesized from African slave rhythms and Iberian harmonies and then blended over five centuries of post-Columbian history into distinct Cuban tunes. Rumba and mambo. Salsa and Latin jazz.

As music aficionados the world over discovered with the release of The Buena Vista Social Club album, music is not exempt from the Cuban time capsule. The performers might have aged, but the tunes themselves remain largely unchanged from pre-revolution days. And once again, like nearly everything else in this timeless metropolis, that’s what makes it so compelling.

Many of the city’s cafes and bars boast some sort of house band, sometimes two or three. And they do not restrict themselves to evening performances. One of the great joys of exploring Havana is being able to pop into places like La Lluvia de Oro (The Golden Ring) or La Dichosa (Lucky) in the middle of a sweltering afternoon for some live music. Kick back a few cuba libres and let your mind wander back to whatever age knocks your socks off.

“Here was a place where anything might happen. Here was a place where something would certainly happen. Here I might leave my bones,” wrote Winston Churchill after an 1895 visit.

Despite 40 years of political turmoil and economic austerity, Havana retains that aura. A city that floats like a dream on the aquamarine Caribbean, where your own imagination is the only limit.